“Ghungroos, Red Anarkalis, and the Resonance of Dance: Breaking Stereotypes in Karan Johar’s Rocky aur Rani ki Prem Kahaani”

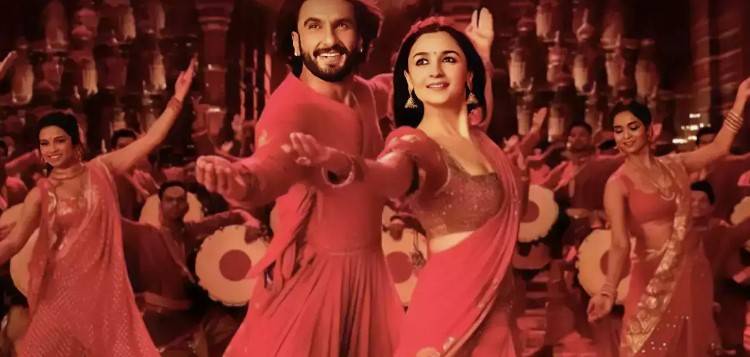

In a viral clip from Karan Johar’s latest directorial venture, “Rocky aur Rani ki Prem Kahaani,” a vibrant recreation of the iconic “Dola Re Dola” song featuring Aishwarya Rai and Madhuri Dixit has captivated attention. The spotlight, however, shines on two men at the heart of the scene, dancing in perfect synchronization. Ranveer Singh channels elements from classical dance, while Tota Roy Chowdhury embodies a kathak dancer who candidly shares his journey, revealing his father’s initial resistance to his passion for dance.

A pivotal moment in the film arrives when Chowdhury asserts, “Art has no gender.” This sentiment resonates beyond the screen, casting a ray of optimism for male classical dancers in India. For many of them, pursuing this tradition often entails navigating patriarchal structures, as classical genres have traditionally been associated with female practitioners.

Historically, cinematic portrayals of male classical dancers, particularly in Bollywood, have leaned towards effeminate and comedic stereotypes. “It mostly involves men cross-dressing as females,” says Vaibhav Arekar, a bharatanatyam dancer based in Mumbai. This is precisely why figures like Suraj Kumar from Ghaziabad welcome Karan Johar’s endeavor to shatter these limiting conventions.

Kumar’s personal journey into kathak began when he attended a performance at 18, connecting deeply with the male performers on stage. “No one in my family had any connection to the arts. Until then, I believed only women danced,” he recalls. However, the absence of male-focused instruction led him to learn through videos of maestros like Pandit Ram Mohan Maharaj. Transitioning to a full-time classical dancer, however, proved challenging, as it involved facing questions, stigmas, and jeers. He was often mocked for carrying ghungroos, and many questioned why he didn’t pursue a more ‘neutral’ art form, such as playing the tabla.

Classical dance forms like kathak and bharatanatyam frequently involve elements like ghungroos, makeup, and dance movements that have historically been considered ‘feminine.’ While certain styles like kathakali have embraced male performers, other classical forms have been slower to evolve, despite the contributions of luminaries like Pandit Birju Maharaj and Kelucharan Mohapatra. Their experiences inspired playwright Mahesh Dattani to create “Dance Like A Man,” a play centered around a man whose father opposes his desire to become a dancer.

Such experiences underscore the influence of patriarchy in delineating societal roles for men and women, notes the dean of the School of Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Furthermore, dance remains ensnared in society’s gendered perceptions of art, shaping expectations for appearance and the types of artistic pursuits deemed acceptable.